what can be done to reduce incurred losses from medicaid

Editor's Notation: This white paper is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Wellness Policy, which is a partnership between the Economic Studies Programme at Brookings and the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based assay leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings. This piece of work was supported by a grant from the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation.

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), states have the option to expand their Medicaid programs to all not-elderly people with incomes beneath 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). To appointment, twelve states have non done so. In these states, people with incomes below 100% of FPL are more often than not ineligible for any form of deeply subsidized coverage considering subsidized Marketplace coverage is typically unavailable to people below the poverty line. Additionally, people with incomes between 100% and 138% of the FPL generally confront college price-sharing—and, until recently, faced higher premiums—than in Medicaid.

The electric current draft of the Build Back Better Human activity (BBBA) proposes to fill this "coverage gap" by expanding eligibility for Marketplace coverage to people below the poverty line in these states. It would also make changes to Marketplace coverage for all people with incomes below 138% of the FPL to make that coverage more "Medicaid-similar," including eliminating almost all premiums and cost-sharing, adding coverage of certain services that are covered in Medicaid merely not typically covered in the Market, and allowing people to enroll in subsidized coverage fifty-fifty if they are offered coverage at work.

While the main beneficiaries of these changes would be low-income people in the coverage gap states, these coverage proposals would also have major implications for hospital finances.[i] This assay uses the rich evidence base produced by country Medicaid expansions to estimate these effects on hospitals.

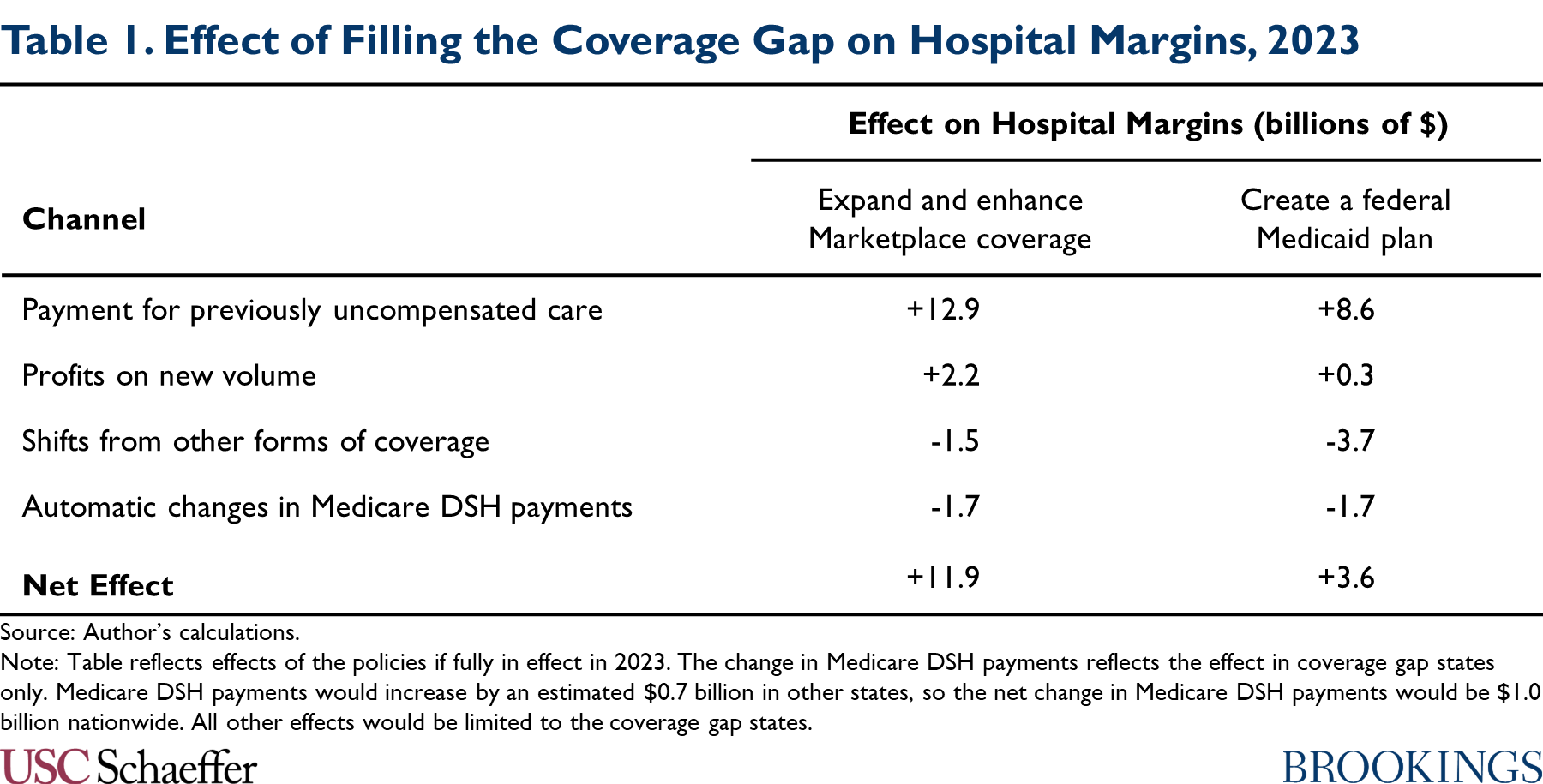

I estimate that aggregate hospital margins in the coverage gap states would improve by $11.9 billion if the proposals in the draft BBBA were fully in consequence in 2023, as summarized in Table i. The main reason for this improvement is that hospitals would now receive payment for some intendance that they already deliver only are not paid for; hospitals would likewise profit from higher volume every bit people gaining coverage sought more care. Those benefits would be partly offset by a minor migration of enrollees out of employer-sponsored plans, which likely pay hospitals more than Marketplace plans. Hospitals in the coverage gap states would besides receive smaller Medicare disproportionate share infirmary (DSH) payments since those payments are ready using a formula that takes into account the national uninsured rate and the allocation of uncompensated care across hospitals, both of which would change. (By contrast, I approximate that hospitals in expansion states would receive larger Medicare DSH payments.)

Hospitals in the coverage gap states would experience a smaller comeback in margins—$3.6 billion in my estimates—if policymakers instead filled the coverage gap by creating a federal Medicaid programme, as envisioned in an earlier House reconciliation proposal. A federal Medicaid plan would likely pay hospitals considerably less than Marketplace plans. As a result, hospitals would receive less revenue for previously uncompensated care, new volume would be less lucrative, and shifts of enrollment from other forms of coverage into the federal Medicaid plan would crusade a larger reduction in infirmary revenues.

The draft BBBA would claw back a portion of the windfall to hospitals created by its coverage gap provisions, specifically past reducing Medicaid DSH payments and restricting Medicaid uncompensated care pools. An of import question for policymakers every bit they finalize reconciliation legislation is whether to go further. Allowing hospitals to retain part of this windfall could, in principle, benefit patients by assuasive some hospitals, especially less-resourced hospitals, to go on operating or invest in improving quality. On the other manus, many hospitals might simply accept higher profits or increase their costs in ways that do not meaningfully do good patients, and recapturing these funds could give policymakers fiscal space to make improvements to the BBBA, such as standing the legislation'southward coverage expansions later on 2025.

The residue of this analysis examines these bug in much greater detail.

Two Approaches to Filling the Medicaid Coverage Gap

This analysis considers two different approaches to filling the Medicaid coverage gap: (one) expanding and enhancing subsidized Marketplace coverage, the approach taken in the draft BBBA; and (ii) creating a federal Medicaid plan, the approach taken in an earlier Business firm proposal. Every bit described in particular below, either approach would offer a new subsidized coverage option to people in coverage gap states with incomes below the poverty line and brand the coverage bachelor to people with incomes betwixt 100% and 138% of the FPL (who currently rely on the Marketplace) more Medicaid-like.[2]

Expand and Raise Marketplace Coverage

The draft BBBA would fill the Medicaid coverage gap past extending eligibility for Marketplace subsidies (that is, the premium tax credit and cost-sharing reductions available for Market plans) to people with incomes below the poverty line, who are generally not eligible for subsidized Marketplace coverage at present. (Nil would modify for people in expansion states since existence eligible for Medicaid would continue to make a person ineligible for subsidized Marketplace coverage.)

The draft BBBA would also implement a diversity of changes to make Market coverage more "Medicaid-similar" for all people with incomes below 138% of the FPL. In particular, changes to the premium taxation credit would ensure that anyone in this group can enroll in the benchmark silvery program without paying a premium, mirroring the fact that Medicaid typically does not accuse premiums.[3] These enrollees would also be eligible for a new, more generous tier of cost-sharing reduction that would offer an actuarial value of 99%, mirroring the nominal toll-sharing allowed in Medicaid, and require plans to comprehend services like non-emergency medical transportation that are mandatory in Medicaid just non in the Marketplace. They would likewise exist exempt from the premium taxation credit "reconciliation" process, which requires people who earn more than during a yr than they expect when they enroll to pay back function of their tax credit.

The draft pecker would also make a diverseness of changes to the Marketplace enrollment process for these enrollees that would bring this coverage into closer alignment with Medicaid. These enrollees would non be subject to the "firewall" that bars about people offered employer coverage from obtaining subsidized Marketplace coverage. They would also exist permitted to enroll in Marketplace coverage at any time during the year, rather than solely during the almanac open enrollment menses.[iv]

Since the coverage made bachelor under these policies would be similar to Medicaid coverage in most salient respects, I presume that this suite of policies would affect insurance coverage and hospital volume (though not the prices hospitals are paid, equally discussed beneath) in a manner similar to existing Medicaid expansions. This assumption allows me to describe on empirical evidence on the effects of existing expansions to estimate how this suite of policies would affect these outcomes.

Still, there are plausible arguments for why the furnishings of these policies could differ from the effects of existing expansions.[5] Notably, the typhoon BBBA does not provide for "retroactive" coverage of services delivered during a period prior to enrollment, coverage that is typically available in Medicaid. Additionally, because the enrollment procedure would be administered by the federal regime via HealthCare.gov, the provisions in the draft pecker would non benefit from any integration with state social service agencies that may be under Medicaid expansion. On the other hand, nether these policies, people in the coverage gap states with incomes above and beneath 138% of the FPL would exist eligible for the same form of subsidized coverage, unlike under Medicaid expansion. This could increment insurance coverage relative to Medicaid expansion by reducing the risk that people who feel income volatility that causes their incomes to rise above or fall below this eligibility threshold experience a loss of coverage.[half-dozen]

The coverage gap provisions in the draft would phase in starting in 2022 and continue through 2025.

Create a Federal Medicaid Plan

Earlier draft reconciliation legislation released in September by the Firm Free energy and Commerce Committee took an alternative approach to filling the coverage gap (for years 2025 and later). That typhoon legislation would have created a Medicaid-like federal plan open to people living in Medicaid non-expansion states who would be eligible for Medicaid if their country adopted expansion.

The House draft envisioned that the coverage offered under this "federal Medicaid program" would closely resemble Medicaid in almost all respects, including benefit design, enrollment rules, and provider payment rates. As such, I assume that this policy would likewise impact insurance coverage and hospital utilization in a manner similar to existing Medicaid expansions, which again allows me to draw on the testify base on the furnishings of Medicaid expansion in estimating the effects of this policy.

As above, there are arguments for why the issue of introducing a federal Medicaid plan could be larger or smaller than the effect of existing expansions. Like a Marketplace-based coverage gap programme, a federal Medicaid program would non benefit from any integration with state social service programs that may be under expansion. On the other hand, considering a federal Medicaid program would be federally administered, it might reduce the hazard of coverage loss among people who experience a alter in programme eligibility when their incomes rise higher up or fall below 138% of the FPL (although, unlike a Market place-based coverage plan, it would non eliminate these transitions entirely).

Policy Baseline

I estimate the effect of each policy option relative to a current constabulary baseline. Notably, that means that the baseline for this assay does non include an extension of the temporary expansion of the premium revenue enhancement credit included in the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act. The effect of the coverage gap policies would likely exist modestly smaller if analyzed relative to a baseline in which the ARP revenue enhancement credit enhancements were extended since those enhancements reduced the premium for the benchmark plan for people with incomes betwixt 100% and 138% of the FPL from just over 2% of income to nada, thereby closing some of the gap between Marketplace coverage and Medicaid coverage for this group.[7]

I too assume that, under current law, no states would prefer (or end) expansion through 2023, the twelvemonth I focus on in my assay. If states did begin or end expansion, the event of policies filling the coverage gap would be commensurately larger or smaller. Similarly, I assume that Wisconsin will continue to offer Medicaid coverage to people with incomes beneath the poverty line through its pre-ACA waiver program. Correspondingly, I simplify the analysis by treating the policies considered hither equally having no effect in Wisconsin; in reality, they would have some effect with respect to people with incomes between 100% and 138% of the FPL, who currently receive Marketplace coverage in Wisconsin.

Estimating Fiscal Effects on Hospitals

Filling the Medicaid coverage gap would bear on hospital finances in several means. Offset, hospitals would now receive payment for some care that they already deliver merely are not paid for. 2d, hospitals would profit from college volume every bit the people who gained coverage sought more care. Third, hospitals would lose acquirement as some people switched into the coverage gap program from private plans that paid higher prices. Fourth, some hospitals would lose Medicare DSH payments since payments under the program depend on the overall uninsured rate in the U.s. and the distribution of uncompensated care across hospitals, both of which would modify. In what follows, I summarize how I guess each of these furnishings and nowadays my results. The appendix provides additional methodological detail.

Payment for Previously Uncompensated Care

Hospitals deliver a large amount of care for which they receive little or no payment. Much of this care is delivered in emergency situations since federal law requires hospitals to evangelize emergency care without regard to the patient'southward ability to pay. Nether a federal programme that filled the Medicaid coverage gap, some currently uncompensated intendance would become eligible for payment.

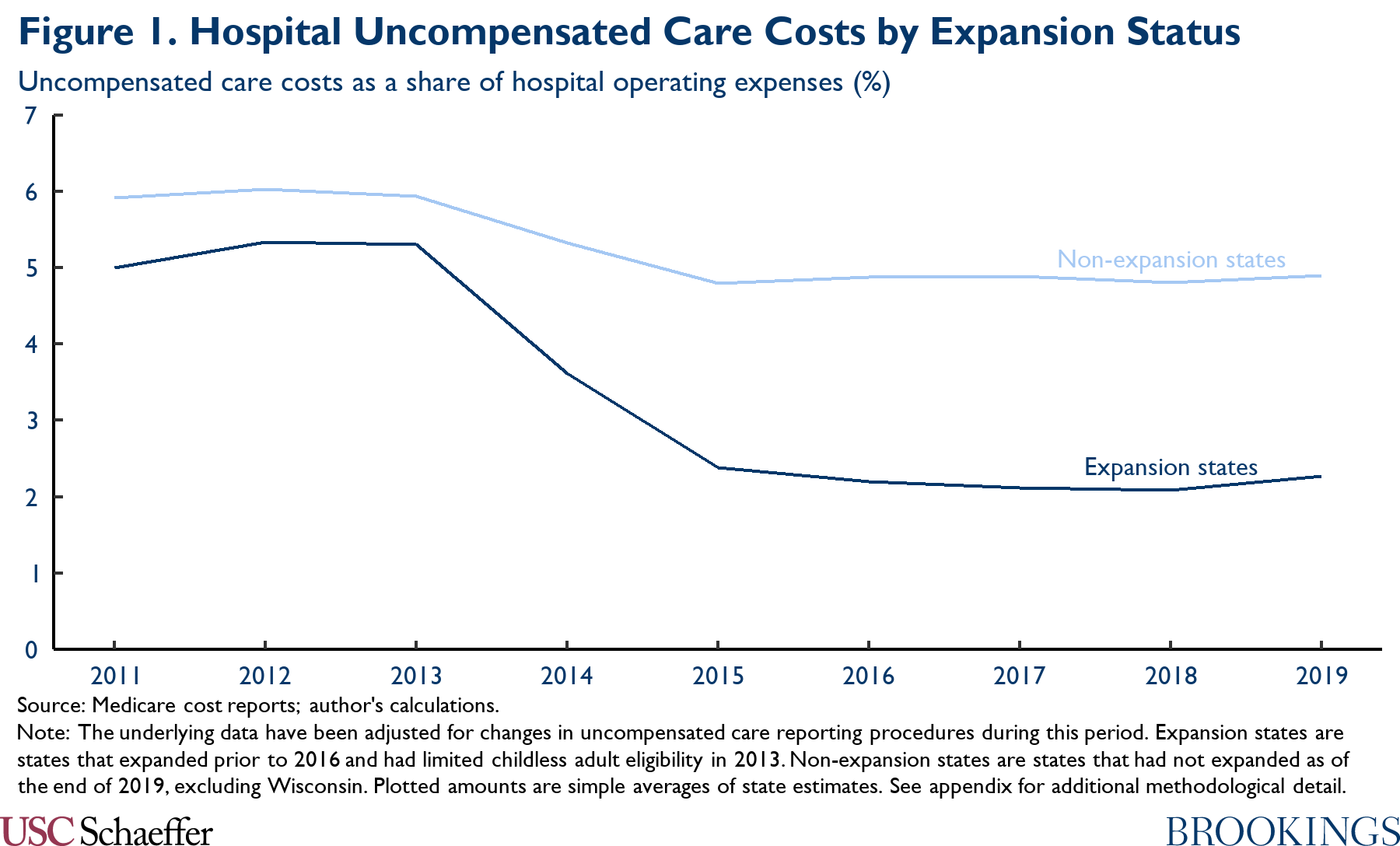

To quantify the resulting increase in hospital revenue, I examine trends in uncompensated care costs (equally reported on hospitals' Medicare cost reports) later on implementation of Medicaid expansion in 2014, following a big prior literature that has estimated the outcome of Medicaid expansion on hospital uncompensated care. Effigy ane replicates the basic finding that emerges from this literature: starting in 2014, the share of hospital expenses consumed by uncompensated care roughshod sharply in states that expanded Medicaid without declining similarly in states that did not expand Medicaid.

As described in the appendix, I employ a deviation-in-differences approach to distill the data underlying Figure i into state-specific estimates of the causal issue of Medicaid expansion on uncompensated care costs; my approach accounts for the possibility that Medicaid expansion (and the ACA'due south other coverage provisions) may accept had dissimilar effects in states with different baseline characteristics. Using the results, I gauge that the uncompensated intendance costs reported by hospitals in the coverage gap states would fall by $ix.4 billion in 2023 if a coverage gap programme were fully in effect in that year.

The ultimate result on hospitals' bottom lines would depend on the prices the coverage gap program paid for the previously uncompensated intendance. I translate the estimated change in reported uncompensated care costs into an estimated effect on hospitals' lesser lines past multiplying past the ratio of the coverage gap plan'south hospital prices to hospitals' average cost of delivering care.[8]

For the scenario where policymakers fill the coverage gap with a federal Medicaid program, I presume that the program would pay hospitals prices equivalent to Medicare's payment rates. Every bit context, research by the Medicaid and Bit Access and Payment Commission (MACPAC) estimated that Medicaid payments to hospitals averaged 106% of Medicare's prices, but this amount includes various forms of supplemental payments to hospitals that might not be fully incorporated into payments made by a Medicaid-similar federal programme.[9] The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) estimates that Medicare's prices currently cover 92% of hospitals' boilerplate costs, implying that the reduction in uncompensated care costs would improve hospital margins by $8.half-dozen billion in 2023 in this policy scenario.[10]

For the scenario where policymakers fill up the coverage gap past expanding Marketplace coverage, estimating the prices hospitals would receive is more challenging since there are no published estimates of the prices that private market place plans pay for hospital care. As a general matter, information technology is commonly believed that these prices are higher the prices paid by Medicare and lower than the prices paid by employer-sponsored plans, with the latter conventionalities often attributed to private market plans' narrower provider networks.[11]

Consistent with that view, enquiry by Lissenden and colleagues using data that private market place insurers submit for run a risk adjustment purposes finds that per enrollee claims spending was 29% lower in the individual market than in large employer plans in 2017, subsequently adjusting for health status differences. A portion of that difference probable reflects differences in utilization rather than prices since narrow networks and other features of private market plans may reduce utilization relative to employer plans (in addition to reducing prices). On the other hand, to the extent that individual market place plans are able to negotiate lower prices than employer plans, it is plausible that those price reductions are concentrated in the infirmary sector since that is where concerns about provider market place power are nearly acute.

In the absence of better data on this question, I therefore assume that the prices private market plans pay hospitals are 29% lower than those paid past employer plans. Research more often than not finds that employer plans pay around twice what Medicare pays for inpatient hospital care and somewhat more than than that for outpatient infirmary care. Adopting the specific estimates of employer prices presented past Chernew, Hicks, and Shah and weighting inpatient and outpatient care equally described in detail in the appendix, I therefore approximate that a Marketplace-based coverage gap plan would pay hospitals 149% of what Medicare pays for hospital services, which would cover 137% of hospitals' average costs. This implies that the reduction in uncompensated intendance costs would total $12.ix billion in 2023 in this policy scenario.

Profits on New Volume

Enquiry examining Medicaid expansion has generally institute that that people who proceeds health insurance under expansion apply more care, and information technology is likely the same would be truthful under a program that filled the Medicaid coverage gap. If the coverage gap program paid hospitals more than their (marginal) cost of delivering that care, this increment in book would translate into higher hospital profits.

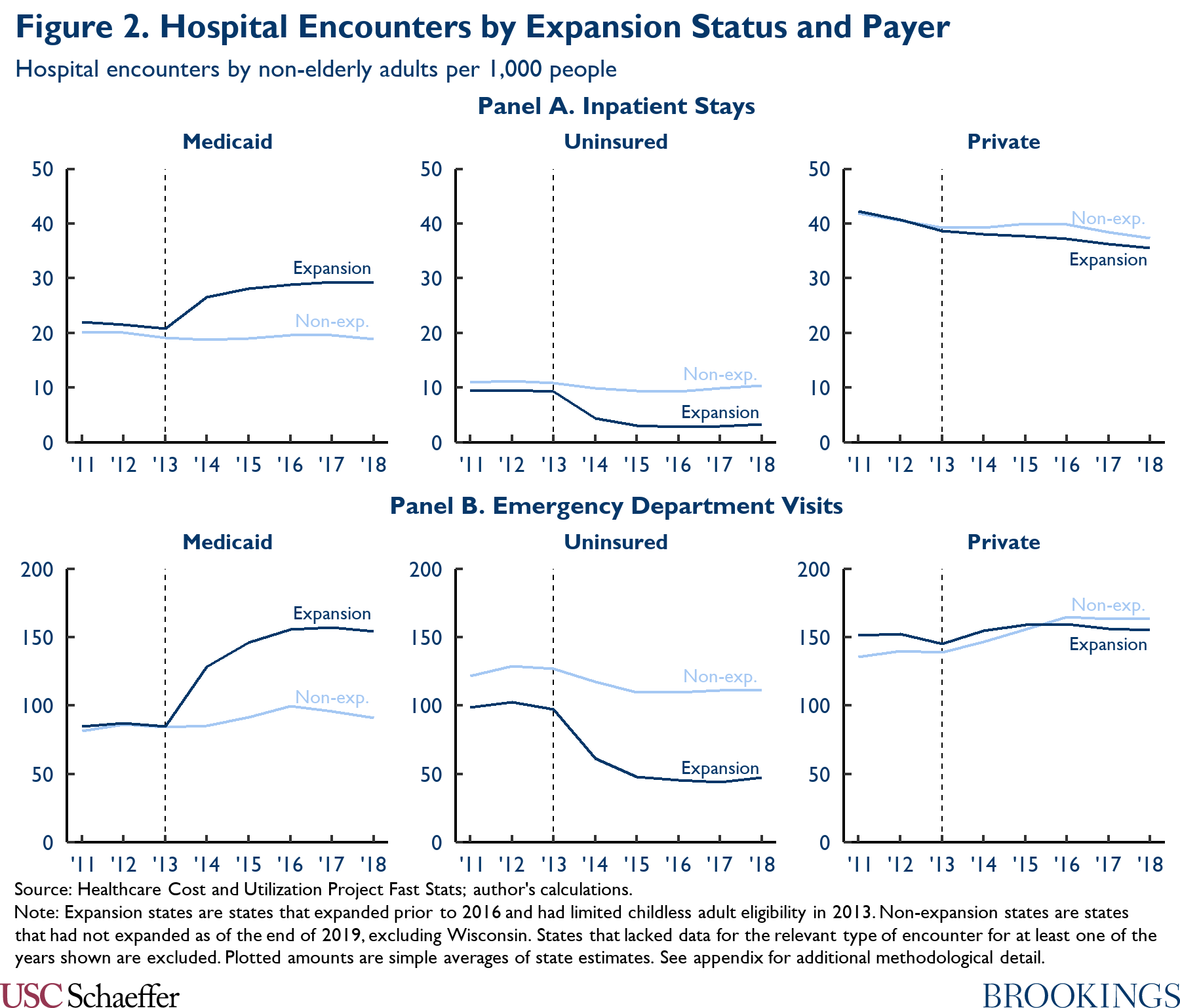

To guess the effect on hospitals' bottom lines, I begin by examining how state Medicaid expansions have affected hospital utilization. To do and so, I use data from the Health Care Price and Utilization Project, like to the arroyo taken past Garthwaite and colleagues. Figure 2 depicts trends in infirmary utilization, disaggregated by payer and utilization blazon. Following expansion, Medicaid expansion states experienced a big (relative) increment in infirmary encounters paid for past Medicaid. This gross increase in Medicaid encounters was commencement in part, but seemingly not fully, by a substantial relative reduction in uninsured encounters and a smaller relative reduction in privately insured encounters.

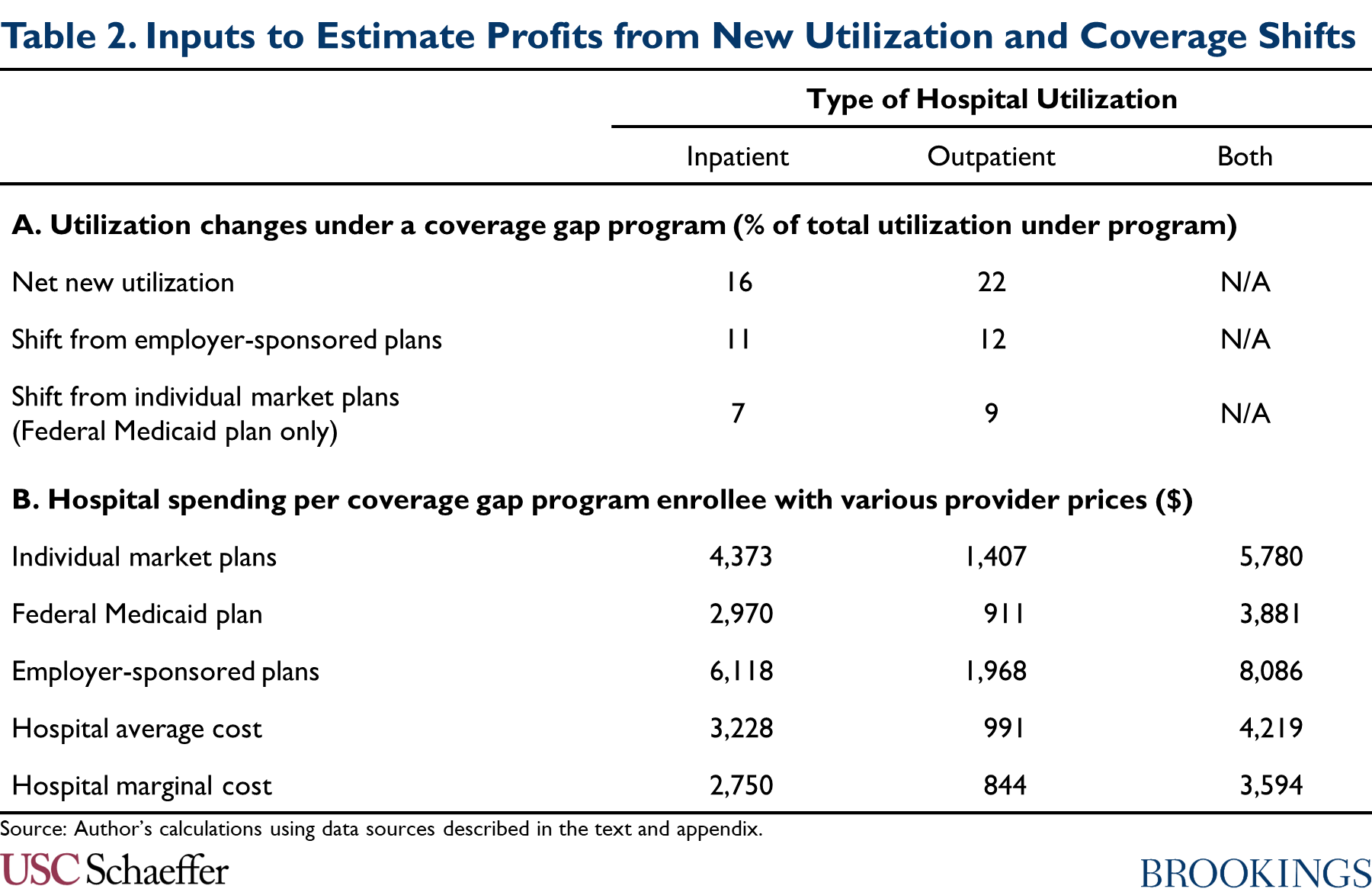

Once more, I apply a difference-in-differences approach to distill the data underlying Figure 2 into state-specific estimates of the causal event of Medicaid expansion on hospital utilization. Using those estimates, I judge that xvi% of inpatient encounters and 22% of emergency section encounters paid for by a coverage gap program would represent net new utilization, as reported in Panel A of Table 2.[12] (In the absence of data on all infirmary outpatient utilization, I use the estimate for emergency department encounters as a proxy for the respective gauge for hospital outpatient encounters overall.)

To obtain an estimate of the resulting effect on hospitals' finances, I multiply these shares past an estimate of the deviation betwixt: (1) the aggregate corporeality a coverage gap program would pay for hospital care; and (2) the aggregate (marginal) costs hospitals would incur to deliver that care. I guess those aggregate amounts by multiplying the acquirement hospitals would receive (and the costs they would incur) per person who enrolled in a coverage gap program by an estimate of full program enrollment.

I estimate per enrollee revenue using the following data: CBO projections of benefit spending on Medicaid expansion enrollees; data from MACPAC, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and Milliman on how spending is allocated beyond services; and the estimates of the prices paid by different payers described above. To estimate hospitals' marginal cost of delivering care, I utilise MedPAC's estimates that Medicare's prices were eight% in a higher place hospitals' marginal cost of delivering services as of 2019. The resulting per enrollee estimates are summarized in Panel B of Tabular array 2. Full details are in the appendix.

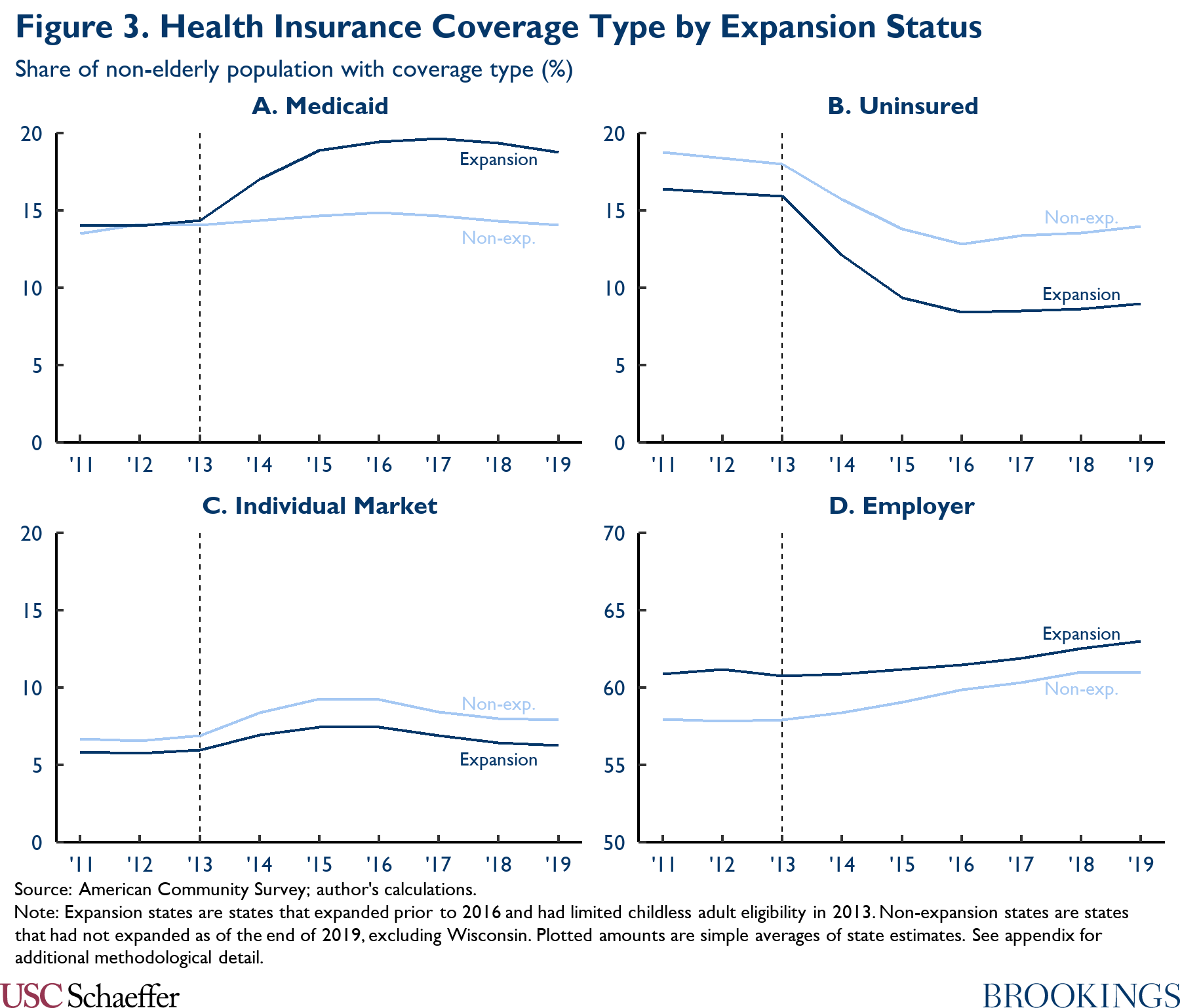

I gauge enrollment in a coverage gap program by comparison trends in Medicaid enrollment between Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states, once more following substantial prior literature; these trends are depicted in Panel A of Figure iii. As in other parts of this analysis, I use a deviation-in-differences arroyo to convert the information underlying Figure 3 into state-specific estimates of the causal effect of Medicaid expansion. Using these estimates, I judge that 5.eight million people would enroll in a coverage gap programme, paralleling the large increase in Medicaid enrollment observed following expansion.

In this fashion, I estimate that hospitals' profits on new volume would amount to $0.iii billion under a federal Medicaid plan and $two.2 billion nether a Marketplace-based coverage gap programme.

Transitions from Other Forms of Coverage to a Coverage Gap Programme

A portion of the services paid for past a coverage gap program would likely be services that are currently paid for by private insurance plans. That would occur for two principal reasons. First, some people who currently have employer-sponsored plans would likely opt for the coverage gap program instead because it offered lower premiums and out-of-pocket costs. 2d, in the case of a federal Medicaid plan, people with incomes betwixt 100% and 138% of the FPL who are currently enrolled in subsidized Marketplace coverage would become eligible for the federal Medicaid programme instead. To the extent that a coverage gap program paid providers less than the plans enrollees shifted out of, infirmary revenues would fall.[13]

To approximate the consequence on hospital finances, I first estimate how much utilization would shift out of other forms of coverage. Equally to a higher place, I use a difference-in-differences approach to distill the information underlying Figure 2 into state-specific estimates of the causal event of Medicaid expansion on infirmary utilization by payer.[xiv] Applying those estimates to a coverage gap program, I estimate that shifts out of employer-sponsored coverage would account for 11% of inpatient utilization and 12% of emergency department utilization under a coverage gap programme, as reported in Console A of Tabular array two. Under a federal Medicaid program, I estimate that utilization that shifted out of individual market plans would business relationship for an additional seven% of inpatient utilization and 9% of emergency department utilization under the plan.

To obtain an guess of the effect on hospital finances, I multiply these shares past an estimate of the departure betwixt the aggregate amount a coverage gap programme would pay for hospital intendance and the aggregate corporeality that would be paid with alternative provider prices (either individual or employer market prices depending on the type of shifting involved). I calculate those aggregate estimates using the estimates of per enrollee hospital spending in Panel B of Tabular array 2 and the estimate of full enrollment in a coverage gap program reported in the concluding section. Using this arroyo, I gauge that hospitals would lose $1.5 billion through these types of coverage shifts under a Market place-based coverage gap program and a larger $3.7 billion through this channel from cosmos of a federal Medicaid plan.

Automatic Changes in Medicare DSH Payments

Medicare makes disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments to hospitals that are intended to beginning hospitals' uncompensated intendance costs. About of those payments are at present set up using a formula established in the ACA.[fifteen] That formula establishes an aggregate national payment pool that scales upward and down proportionally with the national uninsured charge per unit and allocates the puddle across hospitals in proportion to each hospital's uncompensated care costs (as reflected on Medicare price reports). Considering filling the Medicaid coverage gap would reduce the national uninsured rate and uncompensated care costs in the coverage gap states, it would alter the total corporeality and distribution of these DSH payments.

To estimate these furnishings, I brainstorm by estimating the total amount of Medicare DSH payments that will be allocated based on uncompensated intendance costs under current police force; based on the pool established for fiscal yr 2022, I estimate this amount at $7.9 billion in agenda year 2023.[16] Using the estimates of how filling the coverage gap would impact insurance coverage described higher up (and described further in the appendix), I gauge that a policy filling the coverage gap would reduce the national uninsured rate by 12% if fully in effect for 2023 and thus reduce this national puddle of DSH payments past $1.0 billion.

To estimate how this change would be distributed across hospitals, I use the estimates of how filling the coverage gap would bear on hospitals' uncompensated intendance costs that were described higher up to estimate aggregate uncompensated care costs in each land in 2023 under current law and nether these policies. Nether this arroyo, I judge that hospitals in the coverage gap states would receive $one.vii billion less in Medicare DSH payments in 2023 if the coverage gap policies were fully in effect than under current law. Past contrast, hospitals in other states would receive $0.7 billion in boosted DSH payments. This occurs considering the reduction in uncompensated intendance in the coverage gap states would increment the share of uncompensated care accounted for by the expansion states, which would more than than offset the reduction in the size of the national pool of uncompensated-care-based DSH payments.

I note that states also make payments designed to outset uncompensated care costs, including through the Medicaid DSH program and through uncompensated intendance pools ready under Medicaid waivers. If implementation of a coverage gap program caused states to reduce those payments, that could besides reduce infirmary revenues. I exclude those reductions here considering implementing them would generally crave states to implement boosted policy changes. Additionally, states may be less likely to brand these types of cutbacks if federal policymakers take steps to claw back all or part of the benefits to hospitals from filling the coverage gap, so the estimates presented hither may exist a better approximate of the full amount that federal policymakers could recapture from hospitals without leaving them worse off.

A Note on Alternative Estimation Approaches

In this analysis, I approximate the effect of a coverage gap program on hospital finances past explicitly specifying the channels through which a coverage gap program would affect hospitals and then estimating the effects that would arise through each aqueduct. An alternative approach would be to direct estimate the outcome that prior Medicaid expansions take had on hospital profit margins (presumably using difference-in-differences methods similar to those I use in the remainder of this analysis). This "directly" approach has some potential advantages relative to my "disaggregated" approach: it avoids the risk that I might neglect to consider an important channel through which a coverage gap program would bear upon hospitals or that I might incorrectly gauge the furnishings that would arise through one of the channels that I practice consider. Both of these risks are important sources of uncertainty in the estimates I present here.

However, the disaggregated approach I use here has of import advantages that, in my view, outweigh the potential advantages of the direct approach. Beginning, my goal is to estimate how much infinite there is for policymakers to reduce other payments to hospitals without leaving hospitals worse off than they would be in the absenteeism of a coverage gap program. For that reason, my goal is to gauge the "shock" to hospital finances from filling the coverage gap—excluding any changes hospitals make to their operations in response to that shock. Past contrast, the direct approach estimates the realized change in infirmary margins acquired past Medicaid expansion, and, thus, incorporates the issue of any such operational changes. In detail, if positive financial shocks cause hospitals to increment their operating costs, then the realized change in hospital margins would underestimate the initial positive shock.

Second, the disaggregated approach I take here makes it straightforward to account for ways in which a coverage gap program might differ from Medicaid expansion. In item, it allows me to hands account for the fact that a Marketplace-based coverage gap programme would likely pay prices well above Medicaid prices and, thus, have a more positive effect on hospitals' financial position than Medicaid expansion. Related, a disaggregated approach makes information technology clearer how effects on hospital margins would ascend.

Tertiary, the evolution of hospital margins is influenced past many factors other than Medicaid expansion, notably including changes in the commercial pricing environment and changes in input costs. The effects of these factors are potentially big relative to the effect of Medicaid expansion, which creates "background dissonance" that reduces the precision of estimates obtained from the directly approach and opens the door to various forms of bias. By dissimilarity, by building up the overall result on hospital margins from estimates of the outcome on outcomes where the influence of Medicaid expansion is larger in relation to the background noise, my disaggregated approach is less vulnerable (admitting non immune) to this concern.

Regardless, my estimates appear to be broadly uniform with prior research that has used difference-in-differences methods to directly estimate how Medicaid expansion affected realized hospital margins. Notably, Moghtaderi and colleagues estimate that expansion improved the margins of expansion state hospitals by 0.5 pct points, with a 95% confidence interval that extends from -0.5 percentage points to 1.five per centum points.[17] For comparison, I judge that creation of a federal Medicaid plan would issue in a $three.vi billion positive shock to hospital margins if fully in effect in 2023, which translates to i.ane% of projected aggregate patient acquirement in the coverage gap states in that year.[eighteen]

Determination

This analysis estimates that filling the Medicaid coverage gap would meaningfully improve the finances of hospitals in the coverage gap states. I approximate that hospital margins would amend past $11.9 billion relative to current law if the Marketplace-based coverage gap program envisioned in the draft BBBA were fully in effect in 2023. The comeback in infirmary margins would be smaller, but even so substantial—$3.6 billion—if policymakers created a federal Medicaid program, as envisioned in earlier House proposals.

An important question for policymakers as they piece of work to finalize reconciliation legislation is whether they should try to recapture all or role of these benefits to hospitals. Allowing hospitals to retain this windfall could, in principle, benefit patients by allowing some hospitals, particularly less resourced hospitals, to go on operating or to make investments that improved quality of care. On the other hand, many hospitals might simply have college profits or increase their costs in ways that exercise non meaningfully do good patients, and recapturing some of the benefits to hospitals could requite policymakers fiscal space to brand improvements to the BBBA, such as continuing the legislation's coverage provisions past 2025.

The draft BBBA already contains some provisions aimed at clawing dorsum some of the financial benefits to hospitals. Starting in fiscal year 2023, the bill reduces Medicaid DSH allotments by 12.5% in non-expansion states; the resulting reduction in federal funding for Medicaid DSH payments would outset at effectually $400 million per twelvemonth and rise gradually over time.[19] The draft beak also imposes some limits on the telescopic of uncompensated care pools funded via Medicaid waivers non-expansion states. Estimating the affect of those provisions is across the scope of this analysis; however, the total amount of federal funding for existing uncompensated care pools is on track to full only around $4.4 billion per twelvemonth, which provides an upper bound on the potential reduction in federal funding from this provision.[twenty],[21]

It thus seems clear that there is room to claw back more money from hospitals in the coverage gap states without leaving them worse off than they would be without legislation filling the coverage gap. If policymakers wanted to go further in this direction, there are natural options for doing so. For example, they could implement larger reductions in Medicaid DSH payments in the coverage gap states or more tightly limit Medicaid uncompensated care pools. They could also consider reducing Medicare DSH payments in the coverage gap states. Fifty-fifty after the automated reductions in Medicare DSH payments described to a higher place, I estimate that Medicare will still make $3.0 billion in uncompensated-intendance-based DSH payments to hospitals in the coverage gap states in 2023, with similar payments in afterwards years.

Footnotes:

[1] Throughout, I apply the term "coverage gap states" to refer to the twelve not-expansion states other than Wisconsin. Wisconsin has not adopted Medicaid expansion, but offers Medicaid coverage to people with incomes beneath the poverty line through a pre-ACA waiver program, so coverage gap policies would have somewhat different—and generally smaller—effects in Wisconsin than in the other non-expansion states.

[ii] Both proposals also include provisions designed to dissuade existing expansion states from ending their expansions. While a detailed analysis of those provisions is beyond the scope of this slice, I do assume that these provisions would be effective, so neither policy would have directly effects in the electric current expansion states.

[three] For the purposes of this analysis, I consider just the increment in the generosity of the premium tax credit that applies to people with incomes beneath 138% of the FPL, not the broader increases included in the draft BBBA.

[4] The administration recently fabricated an administrative alter that allows people eligible for zero-premium benchmark silvery plans to enroll at any time during the twelvemonth. The provision in the typhoon BBBA provision would, in effect, codify that policy with respect to the coverage gap population.

[five] There are too plausible arguments that the effect of Medicaid expansion could be smaller in the coverage gap states since those states might erect larger administrative barriers to enrollment. Considering federal coverage gap programs would not depend on land cooperation, this would non affect the applicability of evidence from existing Medicaid expansions. However, this line of argument does propose that a federal coverage gap program could have larger effects on the outcomes of interest than Medicaid expansion in these states.

[six] Medicaid expansion itself could be less effective in the coverage gap states than in other states since those states appear to be less motivated to expand coverage. This raises the possibility that feel with Medicaid expansion in other states could overstate the consequence of Medicaid expansion in the coverage gap states and also that federal programs targeted at the coverage gap population (including both the typhoon BBBA proposals and a federal Medicaid plan) could have larger effects relative to Medicaid expansion in the coverage gap states.

[7] While the comparison to a current police force baseline is of interest in its own correct, i analytic advantage of focusing on this baseline is that the baseline policy surround closely resembles the i that existed when almost existing data were nerveless and when most existing Medicaid expansions were implemented. This makes information technology more straightforward to apply experience from the historical period to analyze the result of the coverage gap policies.

[8] This calculation would be exactly correct if reported uncompensated care costs solely reflected the cost of delivering care to uninsured patients—and those patients made no payment at all for that care. In reality, reported uncompensated care costs internet out partial payments from uninsured patients and additionally include price-sharing obligations of insured patients that a hospital is unable to collect. The appendix considers this and related complications and concludes that these problems may engender a downward bias in my estimate of the improvement in hospital finances, but that this bias is likely relatively slight, less than $1 billion under either form of coverage gap program. Thus, I retain the simplified calculation in the principal text for ease of exposition.

[nine] In item, some of these payments are intended to defray a portion of hospitals' uncompensated care costs rather than recoup hospitals for treating Medicaid enrollees. Policymakers might not run across the need to aggrandize the latter type of payments in the context of a program filling the Medicaid coverage gap.

[10] As a cantankerous-check on this estimate, I besides estimated how much revenue hospitals would receive for care being delivered to people who are currently uninsured using the data on hospital volume by payer considered afterwards in this analysis. Under that approach, I estimated that hospitals would receive $14.iv billion for this care under a federal Medicaid program and $21.4 billion nether a Marketplace-based coverage gap program. Because those estimates practise not net out any amounts hospitals are able to collect for care delivered to these uninsured patients (either from the patients themselves or from sources like indigent care programs), they are not directly comparable to the estimates that I derive based on reported uncompensated care costs. Taking business relationship of that difference, still, these estimates are broadly compatible with the uncompensated-care-based estimates.

[eleven] Features of the individual market place other than differences in network breadth may besides affect prices. Notably, enrollees may exist more sensitive to premium differences, which may in turn increase insurers' leverage when bargaining with providers, even holding a plan's network characteristics fixed.

[12] Throughout, when I refer to services paid for by a coverage gap program or enrollment in such a program, I include people with incomes between 100 and 138% of the FPL who already receive Market place subsidies.

[thirteen] Some patients might also transition from having their care paid for by land or local indigent care programs into a coverage gap program. Those transitions are not captured here, but at least in the instance of a Marketplace-based coverage gap program, they would likely generate some boosted financial benefit to hospitals.

[14]The data underlying Figure 2 do non disaggregate utilization in private market and employer-sponsored coverage. Equally described in the appendix, I utilize estimates of the effect of Medicaid expansion on each form of coverage to split apart the overall change in private insurance utilization into its constituent components.

[15] Medicare also makes some DSH payments using a pre-ACA formula based on how many Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income enrollees the hospital treats. Payments under the pre-ACA formula are also one of the inputs used to determine the national pool of uncompensated-care-based DSH payments. I assume that people enrolled in a federal Medicaid program would not be considered Medicaid enrollees for Medicare DSH purposes, and so neither policy considered here would touch on Medicare DSH payments under the pre-ACA formula.

[16] The concluding rule setting Inpatient Prospective Payment System payment policies for federal financial year 2022 establishes an aggregate uncompensated care DSH payment pool of $7.ii billion. I trend that amount forrard to fiscal years 2023 and 2024 using the March 2020 National Health Expenditure projections of Medicare hospital spending, and I then take a 25/75 weighted average of those amounts to get a calendar yr 2023 estimate.

[17] Other studies estimate larger (and statistically significant) positive effects on hospital margins. As Moghtaderi and colleagues note, still, the other studies in this literature have by and large weighted all hospitals as, rather than assigning greater weight to larger hospitals. Since all of these studies agree that Medicaid expansion had larger positive effects on smaller hospitals, studies that use equal weighting may overstate the positive effect on aggregate hospital margins, which is what I aim to approximate here.

[xviii] To estimate aggregate patient revenue in these states in 2023, I begin with an estimate of this amount every bit of 2019 derived from hospital cost reports. I and so trend this amount forward to 2023 using the National Health Expenditure projections of cumulative growth in amass hospital spending from 2019 to 2023.

[19] Total Medicaid DSH allotments for non-expansion states, as published by MACPAC, are $3.3 billion for fiscal twelvemonth 2022, of which 12.5% is $407 million. Under current law, aggregate national Medicaid DSH allotments will be reduced past $8 billion relative to the bones Medicaid DSH formula in financial years 2024-2027. But the linguistic communication in the typhoon BBBA appears to be intended to calculate this additional reduction without regard to those reductions, then this $407 1000000 estimate is likely a reasonable guide to the effect of the draft BBBA provision in futures years. In any case, the nationwide reductions have been repeatedly delayed by Congress and may never have effect.

[20] These pools currently be in Florida, Kansas, Tennessee, and Texas. I obtained information on the total size of each country's pool from the terms and conditions governing its waiver. For Florida, Kansas, and Tennessee, I used the approved amounts for the first year that extends into fiscal year 2023. For Texas, I used the amount currently in upshot since amounts for afterward years accept not been determined. I determined federal funding for each state'southward pool by projecting forwards each state's federal share for financial year 2022, excluding the 6.ii percentage point increase in the federal share in event under the Families Starting time Coronavirus Response Act.

[21] In principle, the reduction in payments to hospitals under these arrangements could exceed the reduction in federal funding if states reduced their contributions to these programs. However, in the example of the uncompensated care pools in particular, the state'due south notional contribution to these programs is often ultimately provided past the hospitals themselves, so the scope for this to occur is limited or non-existent.

Disclosures: The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, equally well every bit an endowment. A list of donors can be constitute in our annual reports published online here . The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its writer(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

Acknowledgments: I thank Loren Adler and Richard Frank for helpful comments on a draft of this piece. I thank Kathleen Hannick and Conrad Milhaupt for excellent inquiry assistance. All errors are my own.

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/essay/how-would-filling-the-medicaid-coverage-gap-affect-hospital-finances/

0 Response to "what can be done to reduce incurred losses from medicaid"

Post a Comment